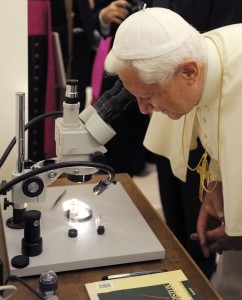

Pope Benedict XVI looks through a microscope during his visit to the headquarters of the Vatican Observatory in Castel Gandolfo, Italy, in this Sept. 16, 2009, file photo. Dialogue and cooperation between faith and science are urgently needed for building a culture that respects people and the planet, the pope said in Nov. 8 remarks to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences.

CNS photo/L’Osservatore Romano via Reuters

Without faith and science informing each other, “the great questions of humanity leave the domain of reason and truth, and are abandoned to the irrational, to myth, or to indifference, with great damage to humanity itself, to world peace and to our ultimate destiny,” he told members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences Nov. 8.

As people strive to “unlock the mysteries of man and the universe, I am convinced of the urgent need for continued dialogue and cooperation between the worlds of science and of faith in building a culture of respect for man, for human dignity and freedom, for the future of our human family and for the long-term sustainable development of our planet,” he said.

Members of the academy were meeting at the Vatican Nov. 5-10.

As science becomes ever more complex and highly specialized, educational institutions and the church have an important role to play in helping scientists broadening their concerns to include the ethical and social consequences of their work, an academy member told Catholic News Service.

“We make scientists today who are excellent specialists and remarkable technicians, but they have little culture in terms of the history of science,” philosophy and ethics, said Pierre Lena, a French Catholic astrophysicist who is working to revamp the way science is taught in schools and universities.

“These technically well-trained people make fantastic discoveries, but they miss the connection with the human person” and often fail to take into account the impact of their discoveries on people and the environment, he said.

The other problem, Lena said, is that the general public often glosses over the importance of science because it is not taught or explained in a way that shows clearly how new knowledge impacts their lives or future.

Scientists usually present their findings by sticking to objective facts without realizing the general public tends to base a lot of their decisions on more subjective reasons like culture, tradition, feelings and religious beliefs, and not just raw data, he said.

Also, people may feel they can’t trust what scientists say because their findings are in constant flux and development, he said.

Lena said scientists need to show that their sense of truth “is not the truth with a capital ‘T,'” but is something that evolves and has limits. Yet, at the same time, a scientific discovery or hypothesis “is not a purely relative opinion” either, but reflects real experimental findings or is based on highly probably statistical calculations, he said.

In his Nov. 8 speech to scientists, the pope said, “The universe is not chaos or the result of chaos, rather, it appears ever more clearly as an ordered complexity which allows us to rise … from specialization toward a more universalizing viewpoint and vice versa.”

While science still has not been able to completely understand the “unifying structure and ultimate unity” of reality, the different scientific disciplines are getting closer to “the very foundations” underlying the physical world, he said.

While the Vatican has done much in terms of reaching out to the world of science through its many conferences and initiatives, more needs to be done by the church on the ground, especially in Catholic schools, in teaching the nature of scientific truth, Lena said.

“Except for the Jesuits, Catholic education was and I think still is cautious about science that might destroy the faith,” with some examples being natural selection and evolution, the possibility of life on other planets and the neurological basis for the psyche, he said.

In general, Catholic education stresses the humanities “because they speak about man, and the good and the bad,” but avoids the more complex or poorly understood modern discoveries and theories of science, he said.

The unfamiliar or quickly evolving terrain of science is one of the reasons why the pope has a science academy — to monitor the latest advancements in different fields, said Bishop Marcelo Sanchez Sorondo, the academy’s chancellor.

He told CNS that it’s critical for the new evangelization to take into account current scientific opinions and positions.

Understanding scientific truths is important “not for any lack on the part of the Gospels or the catechism, but because the intellect is weak and is used to operating from what it already knows,” the bishop said.

By understanding what secularized universities, students or professional fields are thinking, “it’s much easier to be able to help them understand that the truth of faith is not in contrast to these other truths, rather in many cases it strengthens them and gives them new drive, new incentive.”

Lena said scientists who are religious and the church as a whole need theologians to hammer out the Christian response to the many questions that arise in science today, from complex end of life issues to the possibility of life on other planets.

The problem, Lena said, is that much of theology is based on teachings from third- and fourth-century church fathers or 12th-century St. Thomas Aquinas who didn’t face the same social or global challenges today.

“Science is constantly changing our representation of the world. You cannot picture who man is after the discoveries of evolution or neuroscience,” he said.

Theology has to step in and provide some responses, he said, or else Catholics may be tempted to think “science is too dangerous and keep it as far as possible from faith because it threatens” eternal Christian principles that are rooted in outdated concepts or language.

He said if theology could keep pace in providing the Catholic insight and interpretation to modern challenges and discoveries, “then the gap between the beliefs of people and the scientific world” could close.