An American churchman was there when history was made in the Catholic Church

By Jim Wogan

There is a framed and brilliantly colored photo hanging in Cardinal Justin Rigali’s office that shows Pope Paul VI, now a saint, standing on a sunlit stage in Manila, Philippines, vested in white and red, and gesturing with open arms to an unseen crowd of millions.

It resonates with pontifical elegance.

In the same photo, off to the side and among the people standing in the background, is a priest dressed in black clerics, his hands folded in front of him. He is looking out from behind dark sunglasses. The priest is a much younger Cardinal Rigali. The photo was taken in November 1970, many years before Cardinal Rigali would become a Prince of the Church.

Today, Cardinal Rigali looks at the photo and laughs. “They cropped me out,” he said, referring to the official tapestry that hung outside St. Peter’s Basilica when Paul VI was beatified in 2014. The tapestry included the same image of Paul VI, but without Cardinal Rigali and the others.

What happened to Cardinal Rigali and the tapestry might serve as a metaphor for his life in the Church. He was sometimes at the forefront, but often, and very essentially, he was at the immediate periphery of some of the most historic papal events in world and Church history.

For instance, on that historic trip to Manila, the cardinal was near Pope Paul VI when a would-be assassin, dressed as a priest, attacked the pope with a knife. The wound was superficial, but years later His Eminence would witness another, more serious assassination attempt on a pope.

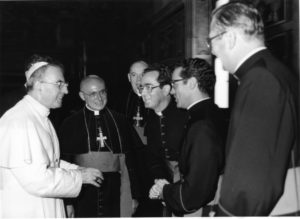

From the very beginning of his priesthood in 1961, providence seemed to suggest that the future cardinal was destined for this path. He arrived in Rome almost immediately after his priestly ordination and was given responsibilities that would eventually lead to his appointment as director of the English Language Section of the Secretariat of State at the Vatican. At the age of 34, then-Monsignor Rigali became the official English language translator for the Holy Father.

President George W. Bush stands with Cardinal Justin Rigali on Oct. 21, 2004 in Downingtown, Pennsylvania. (Photo by TIM SLOAN/AFP via Getty Images)

His work as a trusted member of the Roman Curia brought him elbow-to-elbow with presidents and prime ministers, dictators, Hollywood actors, British royalty, opera stars, rock stars, the wife of a slain U.S. president, labor leaders, military men, and, oh yes, a few saints of the Catholic Church.

He has accompanied popes and served as their translator on visits to roughly 45 countries, some of which later split, morphed into other nations, or don’t exist anymore.

Cardinal Rigali’s ascent through the ranks of the Church, at first glance, might seem rapid, but advice he received early in his vocation cautioned him to take it slow and steady. It came from Hollywood actor Gregory Peck.

“I was a student in Rome, and working at the Vatican as a priest at the time. Gregory Peck happened to be at an event that I was also invited to,” Cardinal Rigali said. “It was a celebration at the American Embassy and he happened to be standing near me. He looked at me, a young priest, and said, ‘Now you have just arrived in Rome, make sure you don’t try to pull off all of this in one semester. Make sure you study.’

“Years later, I met him again. He was in Rome to film The Scarlet and the Black, a great movie about a monsignor in the Vatican who safeguarded and facilitated the escape of Jews in Rome during Nazi occupation. I told him that we had met before. He was very gracious.”

In his role as the pope’s English-language translator, and later as a member of the College of Cardinals, Cardinal Rigali has stood with, and on some occasions spoken to, seven U.S. presidents, beginning with Richard Nixon. The list also includes Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush.

President Reagan met with Pope John Paul II four times. A good number of their discussions focused on nuclear weapons and the end of communism. Cardinal Rigali was present at some of those meetings.

“There was a likeness of opinion between them, especially during that moment

in history,” Cardinal Rigali remembers. “Reagan and the Holy Father did share a great concern for communism.”

Later, after Ronald Reagan’s presidency, Cardinal Rigali sat with him, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, and a few other dignitaries for a private lunch in San Francisco. There were six to eight people there, the cardinal recalled.

“These people were very human, President Reagan in particular,” Cardinal Rigali said.

Even while discussing serious matters, President Reagan’s personality carried the room. “That casual bond with people came through. President Reagan’s method was very simple. At one point he said, ‘I just can’t think of the name of that country …’ and somebody said to him, ‘Russia, Mr. President, Russia.’”

It may have been an indication of Reagan’s declining health.

George W. Bush has met with a pope (John Paul II and Benedict) six times, the most of any U.S. president.

“President Bush was most courteous. He came to St. Louis when I was the archbishop, and he was scheduled to visit my residence. He called at the last minute and was very gracious and asked if we could meet instead at a friend’s house. Bishop Stika was with me on that occasion, and when we drove to the house, before we could even get to the door, Mr. Bush came out and opened the door for me. It is a pleasant memory,” the cardinal remembered.

Cardinal Rigali never met John F. Kennedy, but he was present when the former president’s wife, Jacqueline, had a private audience with Pope Paul VI.

Cardinal Justin Rigali and Jon Bon Jovi share a laugh at a Project H.O.M.E press conference on July 8. 2009 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Photo Jeff Fusco/Getty Images)

Naturally, given the former first lady’s reputation, home decor became a topic.

“I was with Mrs. Kennedy at her private audience with the Holy Father, and it was very moving, and she was very grateful,” Cardinal Rigali said. “There were just a few other people there and among them was the head of the papal household. He asked Mrs. Kennedy, ‘Does madam like the new tapestry in the Vatican?’”

Cardinal Rigali recalled that Mrs. Kennedy responded, speaking French, “Dois-je dire la vérité? (Should I tell the truth?)”

“She said she ‘preferred it the way that it was before.’ She was very grateful and had a good encounter with the pope. You could see that it meant much to both her and the Holy Father.”

The encounters with the powerful and the famous, whether shoulder-to- shoulder or standing politely in the background, always at the ready, are remarkable:

- Queen Elizabeth of England: “For me, being around the queen was, as I remember, a brief experience. After visiting with Pope John Paul II, I believe she came in and greeted the rest of us from afar. Yes, there is certainly something different about the British way of doing things, but they have every right to maintain this.”

- President Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines: “He was not a friend of the poor. The people of the Philippines were exploited under him. I accompanied Pope Paul VI on his trip to the Philippines in 1970. It was his first international trip. Marcos put on a show. He went to a number of the towns we visited and when he didn’t, his wife Imelda would arrive before the pope to meet and greet him and then go on to the next town. Marcos, I think, was a pretty smart person, but he knew it wouldn’t last. He wanted to stay in power as long as he could. I went to the Philippines three times.”

- Idi Amin, dictator of Uganda: “He visited the Vatican and was part of an audience with Pope Paul VI. Anybody that is a ruler, whether he is a good or bad ruler, we don’t want to exclude him. If half of the things that they said about him are true, he wasn’t a good man. But there was every indication that the audience with Pope Paul VI was important. It had ramifications for the people of the country. An audience with a pope can be a way to make impact for good.”

- Diplomat and former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger: “In the years I was the pope’s interpreter, I was with Secretary Kissinger numerous times. He often came to the Vatican as representative of the president and was received with great honor.”

- On nudging world leaders to push diplomacy: “The answer has to be yes. But the pope would not say, ‘Let me tell you how things are. We know your record here.’ But absolutely I was involved in diplomatic conversations more than a few times. I feel Mr. Kissinger wanted to see me because he felt he could explain ideas to me. He was a precise man, and it was a good arrangement for communicating.”

- Teresa of Kolkata: I was with her on a number of occasions. I distinctly remember being with her at Castel Gandolfo, the summer residence of the pope. I was there with my brother Norbert, who was also a priest. We were each given rosaries, but Mother Teresa wanted all of them, and an icon of the Blessed Mother she had seen hanging in the papal chapel, not for herself, but for others. She didn’t get them, but that was Mother Teresa. She was a marvelous woman. She knew the pope, and he was always happy to see her and was always impressed with what she represented.”

- John XXIII: “He was pope when I first arrived in Rome and, in effect, I worked under him during the first two sessions of Vatican II. I never spoke to him, but I certainly made up for it with the other popes,” His Eminence said smiling.

- Rock star Jon Bon Jovi: “We were at a gathering together in Philadelphia. We were on stage sitting next to each other and we chatted and shared a few laughs. Bon Jovi wasn’t performing, but he was trying to assist in this charitable effort. He was a very nice guy. No, I can’t say that I actually listen to his music.”

Cardinal Rigali has had dinner with Polish labor leader and President Lech Wałęsa. He was there when opera great Luciano Pavarotti sang for Pope John Paul II. He was in attendance on the occasions when Pope John Paul II met Protestant evangelical leader Billy Graham.

He also remembers his first meeting with Cardinal Albino Luciani, who would become Pope John Paul I.

Cardinal Rigali worked for four popes during his time at the Vatican, including John Paul I, pictured above in 1978.

“As a member of the Office of the Secretariat of State, I was asked to attend a meeting of all of the cardinals on a Sunday afternoon at the Vatican because there were going to be many different languages spoken. It was 1978, obviously not long after the death of Pope Paul VI. I drove to the Vatican and I was a little bit early arriving. I was one of the first non-cardinals in the room. Cardinal Luciani was one of the first cardinals to arrive. So we sat down and talked. He was very nice and I remember saying, ‘Wow, he is very impressive.’

This was just a few days before he was elected pope (as Pope John Paul I). That was the first time I met him. He was so very papal.”

Less than five weeks later, Pope John Paul I was dead. As a high-ranking member of the Vatican Curia, Cardinal Rigali worked with him that day and was among the last people to speak to him.

In the early days of his priesthood, Cardinal Rigali participated in one of just 21 ecumenical councils in the 2,000-year history of the Catholic Church — Vatican II.

Seventeen years later, he was a witness to one of the Church’s most terrifying moments — the assassination attempt on Pope John Paul II on May 13, 1981.

“Yes, I heard the shots,” Cardinal Rigali said in a recent interview on the patio of a residence that he now shares with Bishop Richard F. Stika. The interview took place on April 12 — one month and a day from the 40th anniversary of that horrific event.

“I was on the steps of St. Peter’s Basilica and the pope was coming in my direction. I was with his entourage, waiting to announce the pope’s arrival in English to this massive crowd. I saw a monsignor I knew standing in the first row of spectators, but behind a barrier. I went down to talk to him and there was a gendarme, a security officer, standing next to us.

“We saw it happen and the gendarmes ran toward the pope’s open vehicle, it wasn’t very far away at that point. This particular guard ran to the pope’s vehicle and then he followed it, running.”

The memory is still so vivid that Cardinal Rigali is mapping the actions of the vehicle and the position of the guard on the table at which he is sitting four decades later.

“I stayed at the stage area, where the pope was going to address the audience. There was a lot of confusion and clearly people were emotional. First, in English and then other languages, we began to make announcements and we led the audience in prayer.”

“I don’t know how long it was, maybe an hour, perhaps 45 minutes, but we received a communication that the Holy Father had arrived at Gemelli Hospital. I was able to announce that to the audience in English. I said that the Holy Father was alive … and we continued to pray for him.”

In Cardinal Rigali’s office at the Chancery in Knoxville, not far from that photo of Pope Paul VI in Manila, are a series of bookcases that contain theological writings, homilies, books of the Church, and binders that contain the type-written details of Cardinal Rigali’s journeys with the popes; documents that attest to his own historic, apostolic journey.