In Andrew Johnson, 19th-century Catholics found an ally, support

By Emily Booker

As the nation prepares to transition from its 46th president to president No. 47, history is telling us that one parish in East Tennessee had a U.S. president to thank for its establishment.

President Andrew Johnson, who succeeded Abraham Lincoln, was born on Dec. 29, 1808, in Raleigh, N.C., settled in Greeneville, and died on July 31, 1875, in Elizabethton. (WikiCommons)

President Andrew Johnson, whose birthday is celebrated on Dec. 29, began his career as a tailor in Greeneville. He was not committed to any particular denomination, though he attended the Methodist church with his wife, Eliza. He was comfortable visiting a variety of churches and supported various churches’ efforts.

He also staunchly defended the Constitution, including the freedom of religion.

Andrew Johnson served as a U.S. House representative for Tennessee from 1842-1852. At this time, the Know Nothing movement was espousing heavy anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiment. Mr. Johnson strongly defended Catholics against the bias and propaganda.

In a debate in the House in 1845, he said, “The Catholics of this country had the right secured to them by the Constitution of worshiping the God of their fathers in the manner dictated by their own consciences. They sat down under their own vine and fig tree, and no man could interfere with them. This country was not prepared to establish an inquisition to try and punish men for their religious belief. … Are the bloodhounds of persecution and proscription to be let loose upon foreigners and Catholics because some of them have acted with the Democratic party in the recent contest? … From whence or how was obtained the idea that Catholicism is hostile to liberty, political or religious?”

He then quoted George Washington, “I hope ever to see America foremost among the nations of the earth in examples of justice and liberality; and I presume my fellow citizens will never forget the patriotic part which Catholics took in the accomplishment of their revolution and the establishment of their government, or the important assistance which they received from France, in which the Catholic religion is professed.”

Defending the faith

As governor of Tennessee, Andrew Johnson continued to defend Catholics against the political slander of the Know Nothings.

“If objection to tolerating the Catholic religion be because it and its followers are foreign, who was John Wesley and where did the Methodist religion have its origin? If John Wesley were alive today and here, … Know Nothingism would drive him and his religion back to England whence they came because they were foreign. … And so, with Martin Luther, the great Reformer; he would have been subjected to the same proscriptive test,” he said in a speech in Murfreesboro in 1855.

Gov. Johnson found Catholics to be reliable, working-class people. Coming from a poor, working-class background himself, he sympathized with the issues faced by the Irish Catholics he met. He also found in them political allies.

After serving as governor and military governor of Tennessee in Nashville, Gov. Johnson became vice president of the United States in 1864 and moved to Washington, D.C.

After the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865, Vice President Johnson was thrust into the role of president of the United States and given the overwhelming task of actually uniting the states following the division and violence of the Civil War.

The shared tombstone for Lillie and Sarah Stover, Andrew Johnson’s granddaughters, in Johnson National Cemetery has influences of Catholic architectural style, particularly the arches that are unique to this period in history. The granddaughters, who lived in the White House during his presidency, later attended Catholic school. (Photo Emily Booker)

While serving in D.C., President Johnson’s children and grandchildren joined him in the White House.

Though President Johnson had never received any formal education, he greatly valued education and sought to provide the best for his sons, daughters, and grandchildren. Some members of his family received their education through Catholic schools.

Andrew “Frank” Johnson Jr., the youngest of the Johnson children, attended the Jesuit-run Georgetown Academy in Washington, D.C.

Mary Stover, President Johnson’s youngest daughter, was widowed during the Civil War. She and her children lived in the White House during her father’s presidency. It is not known when, but it is believed that at some point Mary Stover and her daughters, Lillie and Sarah, joined the Catholic Church.

On July 2, 1866, President Johnson, accompanied by both of his daughters, conferred the honors awarded to the female students at the Academy of the Visitation.

The Washington newspaper The Evening Star reported on Mary Stover and one of her daughters attending Mass at St. Aloysius Church on April 22, 1867.

In the 1870s, Sarah Stover attended St. Bernard’s Academy, operated by the Sisters of Mercy in Nashville.

The tombstone for Lillie and Sarah Stover in the Andrew Johnson National Cemetery in

Greeneville is designed in a style representative of Catholic architecture, with bold arches and intricate inlay.

A new church in Greeneville

After his time as president, the Johnson family returned to upper East Tennessee in 1869. There were not many Catholic families in the area at the time. The pastor of Immaculate Conception Parish in Knoxville would occasionally travel to several towns in upper East Tennessee to celebrate Mass and baptize children.

However, the expanding railroad system was bringing more people to the region, notably Irish Catholic rail workers and their families.

Also in 1869, Felix Reeve donated land on High Street in Greeneville (now College Street) to Bishop Patrick Feehan of the Diocese of Nashville to build a Catholic church in Greeneville. Mr. Reeve asked President Johnson for a donation to the effort because the “Catholic Church has well-grounded claims on all who are friendly to constitutional and liberal government. For that body of Christians is, and ever has been, democratic and conservative.”

President Johnson responded with the largest single donation to the project: he donated $500 for the church, the equivalent of almost $12,000 today.

Perhaps it was a political calculation to gain Catholic Democratic support, perhaps there were Catholics in his own family who encouraged him to donate, or perhaps it was his personal openness to Christian worship of all stripes (he also contributed money or land for other churches in Greeneville). Whatever his personal motivation, the former president’s support helped establish the first permanent fixture of Catholicism in Greeneville.

On Sunday, Oct. 16, 1870, Bishop Feehan dedicated St. Patrick Church in Greeneville, with President Johnson sitting in the front row. A special train ran that morning from Knoxville to Greeneville to accommodate the many people who wished to attend.

The Knoxville Press and Messenger covered the dedication of the church:

“Upon our arrival we found an immense multitude present, all eager to witness the splendid and imposing ceremonies. … The procession slowly moved around the exterior of the Church chanting the usual psalms, the bishop in the meantime sprinkling the walls with holy water. The procession afterwards returned and entered the main entrance, when the litanies were repeated, and the other rite performed.

“Then the people entered and the church was, in a moment, densely crowded; those who could gain admittance were content with any available spot; many perched themselves on the window sills, others packed themselves around the doors and in the vestry rooms, while the largest portion of those present were unable to obtain any view at all.

“Among those present, we observed Ex-President Andrew Johnson, who was invited to the front seat. The interior by the sacred edifice looked very chaste and bore evident marks of having been built by master workmen, who exercised most unusual skill in its construction.”

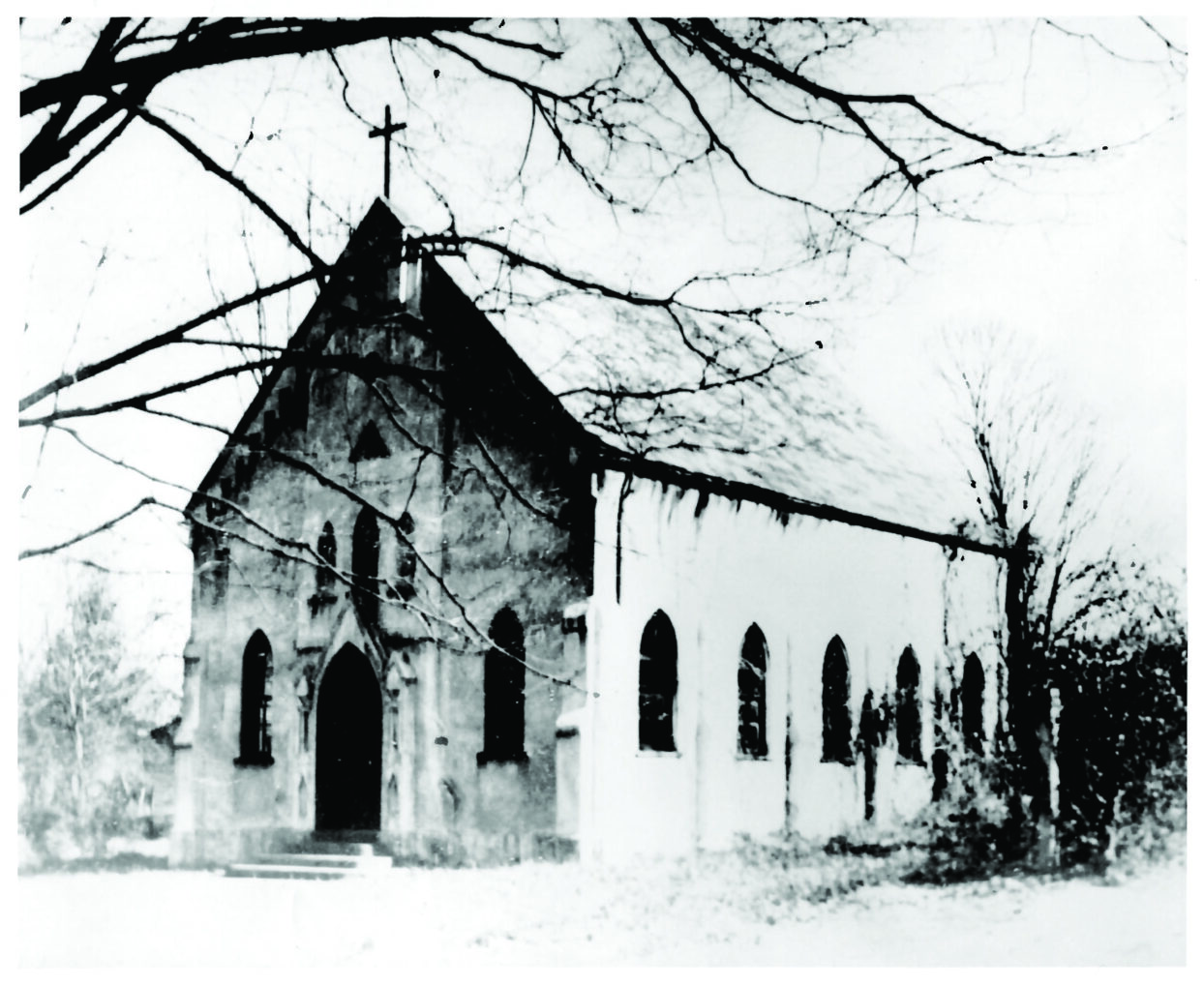

St. Patrick Church in Greeneville is seen as it looked at the turn of the 20th century. Irish Catholic railroad workers, who brought Catholicism to the region, made up a large portion of the church’s early membership. (Photo from The East Tennessee Catholic archives.)

After the dedication Mass, Bishop Feehan administered the sacrament of confirmation to about 40 people, according to The Press and Messenger.

The brick church was 28 feet wide and 40 feet long. It was renovated twice in the following decades, including covering the brick work with white stucco.

Unfortunately, several St. Patrick Parish families moved away from Greeneville, many following the work of the railroad further west. The parish continued to offer Mass semi-regularly, often celebrated by a visiting Dominican priest from Johnson City, for the small Catholic population there.

In 1949, the Greeneville Telephone Service bought the property on College Street from the diocese. In 1950, St. Patrick Church was torn down.

The Catholics of Greeneville continued to worship, meeting in homes and the local theater until the building of Notre Dame Church on Mount Bethel Road in 1955.

But the memory of Greeneville’s first Catholic church lives on in the memory of the community. If one looks in the Notre Dame nave, there is a small stained-glass window on the Marian side near the sanctuary with an image of St. Patrick Church, a remembrance of the first Catholic church in Greeneville that had a U.S. president as its supporter.